The impetus behind the Wisdom Circle is the belief that scientific knowledge, and the technology it supports, is not enough to enable us to negotiate the future as a human race. I am supported in this by none other than David Attenborough. He finishes his latest book, and the Netflix presentation that goes with it, with these words, The living world has survived mass extinctions several times before. But we humans cannot assume we will do the same. We have come as far as we have because we are the cleverest creatures to have ever lived on the Earth. But if we are to continue to exist, we will require more than intelligence. We will require wisdom (my emphasis) (Attenborough 2022:220) The mechanical world view, which could be said to have begun when we human beings first began to make tools with which we could change the world around us, was enhanced manyfold with the rise of modern science and the delineation of the physical world through mathematical symbols. It has culminated in artificial intelligence. So successful has this world view become that most other world views have been abandoned or at least challenged. Some think a profound hubris has taken over human consciousness. Yet, as we have seen, such a world view exists on very shaky ground (see last month’s blog). So much of what makes our lives truly human is not subject to either science or technology, but rather personal experience through relationship. This is where we learn wisdom. Our failure to see this and really value this is now critical. There was a break-through for me this week with the publication of Humanity’s Moment: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope by Australian Joelle Gergis. She is a lead author on the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report published this year. Her book is both scientific and human, passionately humane in fact. It is as if a leading scientist has decided the re-join the human race and not just play the detached observer from the ‘view from nowhere’. She is letting herself really feel the feelings that she feels working as a leading scientist facing humanity’s greatest challenge, but then also taking us in on her journey of her inner world. She ends her book with the very same quote from David Attenborough above. But whereas Attenborough only sees the ‘wisdom horizon’, Gergis plunges in. What she is doing is ‘getting wisdom’, valuing science completely but understanding its limits while at the same time embracing the equal importance of feeling (the arts) and personal relationship. Her struggle has been to re-find faith in humanity, knowing what she knows as a scientist in the face of indifferent politicians and blatantly self-interested fossil fuel industries. Did you know that fossil fuel lobbyists were the largest contingent at COP 26 in Glasgow? Did you know that in Australia more money is spent on fossil fuel subsidies than on the Australian army? I very warmly recommend both these books as essential reading for anyone interested in wisdom and concerned about what is happening in our world. May many more scientist’s do what Gergis is doing, but as she herself recognises, many scientists, especially male ones, have trouble feeling their feelings and are locked in the illusory world that scientific knowledge is objectively true regardless of our experience, a ‘view from nowhere’ as the philosopher Thomas Nagel put it, like a ‘god’ who is entirely separate from his creation and only observes it neutrally. Such a view is no longer tenable. Iain McGilchrist is also doing what Attenborough and Gergis are doing, trying to grasp what it is to be fully human in our modern world in the face of the global challenges we face. He is accepting the full intellectual side of this, bringing together science, philosophy, the arts and personal relationship, in the search for wisdom that matters and makes the differences we so desperately need. But he is much clearer I think about the problem we face, at least as he sees it. Whereas much traditional religion, especially the monotheistic types, sees the problem as sin, desire and disobedience, entrapping us in our egocentric selves, McGilchrist anchors our dilemma in our very bodies, in the bi-cameral nature of our brains. Our brains are the way they are because they evolved this way to enable us to survive in a world where we need to eat but also need to avoid being eaten, to put it bluntly. The Left Hemisphere (LH) evolved to help us manipulate the world to enable us to eat, to be aware of the parts; the Right Hemisphere (RH) evolved to help us keep an eye on the bigger picture, the whole, to enable us to avoid being eaten. Whether McGilchrist is right about all this or not, he does appear to be right in his analysis of the bi-cameral nature of the brain. Both hemispheres are involved in just about everything we do, but they each have a very different take on the world. Each hemisphere is capable of consciousness in its own right, but it is in the working of these together that our full human consciousness emerges. But the hemispheres are not equal in this. In proper balance, the RH is primary and the LH serves it. In McGilchrist’s view this proper balance is not the case in our modern world. It has been reversed. The LH has taken over and has in part negated the RH. This is our problem. We have to re-find and nurture the primacy of the RH. We need wisdom and not just knowledge. In fact we need to value wisdom over knowledge, relationship over objective isolation. The brain is, importantly, divided into two hemispheres: you could say, to sum up a vastly complex matter in a phrase, that the brain’s left hemisphere is designed to help us ap-prehend – and thus manipulate – the world; the right hemisphere to com-prehend it – see it all for what it is……. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that while we have succeeded in coercing the world to our will to an extent unimaginable even a few generations ago, we have at the same time wrought havoc on that world precisely because we have not understood it. 10 ...indeed, each hemisphere deals with absolutely everything – just in a reliably different way. The character and sheer extent of that difference, as well as its significance for the future of our civilisation, formed the subject of The Master and His Emissary. And that difference could be seen as rooted in a difference in attention, as I shall explain. 32…..the bi-hemispheric structure of the brain makes possible attending to the world simultaneously in two otherwise incompatible ways. 34 McGilchrist goes into great detail, carefully justified with evidence both scientific and philosophical, for the different roles and functions of the two hemispheres of our brains. Here is one of his summaries, some points of which we will examine more closely in the Wisdom Circle. (the numbers refer to pages in The Matter With Things). 1. The LH is principally concerned with manipulation of the world; the RH with understanding the world as a whole and how to relate to it.53 2. The LH deals preferentially with detail, the local, what is central and in the foreground, and easily grasped; the RH with the whole picture, including the periphery or background, and all that is not immediately graspable. The importance of the global (RH)/local (LH) distinction cannot be overstated. It is also extremely robust.54 ‘Perhaps the most compelling distinction between local and global visual processing is the differential lateralisation in the brain’;55 ‘evidence to support this hypothesis comes from a wealth of data’.56 3. The RH is on the lookout for, better at detecting and dealing with, whatever is new, the LH with what is familiar. VS Ramachandran calls the RH the ‘devil’s advocate’, since it acts as an ‘anomaly detector’, on the lookout for what might be erroneously assumed by the LH to be familiar.57 4. The LH aims to narrow things down to a certainty, while the RH opens them up into possibility. The RH is able to sustain ambiguity and the holding together of information that appears to have contrary implications, without having to make an ‘either/or’ decision, and to collapse it, as the LH tends to do, in favour of one of them. 5. In line with this, the style of the RH is altogether more circumspect than that of the LH, which tends to be less self-critical.58 6. The LH tends to see things as isolated, discrete, fragmentary, where the RH tends to see the whole. The LH tends to see things as put together mechanically from pieces, and sees the parts, rather than the complex union that the RH sees.59 7. The LH’s world tends towards fixity and stasis, that of the RH towards change and flow.60 8.The LH tends to see things as explicit and decontextualised, whereas the RH tends to see them as implicit and embedded in a context. As a result, the LH largely fails to understand metaphor, myth, irony, tone of voice, jokes, humour more generally, and poetry, and tends to take things literally.61 9. There is a tendency for the LH to prefer the inanimate, the RH the animate. Machines and tools are alone coded in the LH, too, while the animate is coded by both hemispheres, though preferentially by the RH.62 10.The RH understands narrative. The LH, if offered a story whose episodes are taken out of order, tends to regroup them so as to classify similar episodes together, rather than reconstruct them in the order that has human meaning.63 11. Both hemispheres need to categorise, but do so according to different strategies. The LH tends to categorise using the presence or absence of a particular feature; the RH tends to do so by reference to unique exemplars, using what Wittgenstein called a ‘family resemblance’ approach – it sees the Gestalt.64 12. More general categories are dealt with preferentially by the LH, more fine-grained ones, as one approaches more closely uniqueness, by the RH. Damage to the RH can lead to a loss of the sense of uniqueness or the capacity to recognise individuals altogether.65 13. The RH contains the ‘body image’ (this is a slightly misleading neuropsychological term which refers not just to a visual image, but to a multimodal schema of the body as a whole). The LH tends to focus on parts – arms, legs and so on – out of which the body must then be constructed. The RH tends to process in a more embodied, less abstract fashion than the LH. The RH is also superior at reading body language and emotion expressed in the face or voice.66 14. The LH is superior for fine analytic sequencing and has a larger linguistic vocabulary and more complex syntax than the RH. Pragmatics, the ability to understand the overall import of an utterance in context, is, however, a RH function. Understanding prosody, the musical aspect of language, its tone, inflection, etc, depends to a very large extent on the RH.67 15. For most of us, music is very largely the province of the RH, the LH dealing only with simple rhythms.68 16. The RH is essential for ‘theory of mind’: that is to say that it is better able to understand another’s point of view.69 17. The RH is essential for empathy.70 18. In very general terms, both emotional receptivity and expressivity are greater in the RH.71 19. The RH is better at seeing things as they are pre-conceptually – fresh, unique, embodied, and as they ‘presence’ to us, or first come into being for us. The LH, then, sees things as they are ‘re-presented’, literally ‘present again’ after the fact, as already familiar abstractions or signs. One could say that the LH is the hemisphere of theory, the RH that of experience; the LH that of the map, the RH that of the terrain.72 20. The LH is unreasonably optimistic, and it lacks insight into its limitations. The RH is more realistic, but tends towards the pessimistic.73 How does all this fit within your thinking (and feeling)? Does it help? Can we bring ourselves forward in conversation as passionately as Attenborough, Gergis and McGilchrist in our own way and lives? Can we find ways to live this out in our very challenged but largely denying world?

0 Comments

It All Depends on What We Attend To

Last month I mentioned a turning point in my own consciousness of the world and the world when I mistook a leaf for a frog. But in that split-second moment I had really seen a frog. I imagine we all have experiences like this from time to time, and think nothing more of it. But at the time I was reading the polymath Gregory Bateson, and the following passage hit home because of that experience. When somebody steps on my toe, what I experience is, not his stepping on my toe, but my image of his stepping on my toe reconstructed from neural reports reaching my brain somewhat after his foot has landed on mine. Experience of the exterior is always mediated by particular sense organs and neural pathways. To that extent, objects are my creation and my experience of them is subjective, not objective. It is not a trivial assertion to note that very few persons, at least in our occidental culture, doubt the objectivity of such sense data as pain or their visual images of the external world. Our civilization is deeply based on this illusion. (Bateson 1980:39) I think as moderns interested in Wisdom it is vital we have some understanding of this illusory nature of our civilization, and how we got to here. Some have gone further than the illusory. The famous astrophysicist Arthur Eddington, the first translator of Einstein into English, wrote, We all share the strange delusion that a lump of matter is something whose general nature is easily comprehensible whereas the nature of the human spirit is unfathomable. (17) People generally are not aware that our direct actual experience is mental not material, both of ourselves and the world. Eddington put it this way. In comparing the certainty of things spiritual and things temporal, let us not forget this—Mind is the first and most direct thing in our experience; all else is remote inference. (18) This takes us to the heart of our dilemma in the modern tension between knowledge and wisdom. The neuro-philosopher Philip Goff put it this way. The quantitative conception of science bequeathed to us by Galileo has been extraordinarily successful. By focusing exclusively on what can be captured in mathematics, scientists have been able to construct mathematical models of nature with ever greater predictive power. These models have enabled us to manipulate the natural world in undreamed of ways, resulting in extraordinary technology. We are now living through a period of history in which people are so blown away by the success of physical science, so moved by the wonders of technology, that they feel strongly inclined to think that the mathematical models of physics capture the whole of reality. (172) But the mathematical models of physics don’t capture the whole of reality, far from it. The reality of consciousness is much more. As a culture we are convinced of the reality of the external physical world that we manipulate with our technology and science and think we understand, while increasingly denying our own experience of an inner life, of our own consciousness which is so much more than the abstracted physical world bequeathed to us by modern science. I mean the world of the imagination, of intuition, of values, of love and a sense of purpose. What can add insult to injury is that modern mathematical science, real science as some would say, tells us nothing of the intrinsic nature of our world. It deals only with symbols. Newton was the first to admit he had no idea what gravity really was in itself. The mathematics worked. So why worry said our culture. And this attitude has prevailed right down to the Standard Model of quantum mechanics, a world of physical symbols. Models are still important to science but symbols more so, particularly at the edge between the physical and the mental that the quantum world is. Eddington again. ..if today you ask a physicist what he has finally made out the æther or the electron to be, the answer will not be a description in terms of billiard balls or fly-wheels or anything concrete; he will point instead to a number of symbols and a set of mathematical equations which they satisfy. What do the symbols stand for? The mysterious reply is given that physics is indifferent to that; it has no means of probing beneath the symbolism. To understand the phenomena of the physical world it is necessary to know the equations which the symbols obey but not the nature of that which is being symbolised. (15) But we can experience the intrinsic nature of our own consciousness. It is the thing of which we are most certain. My experience is me. And from it I infer a world that is real to me, and as much as I may value the inferences of science, my world is bigger than the physical, a world that can’t be explored by scientific symbols but by metaphor, silence, poetry, art, paradox and values, by the personal. I can value the scientific symbols as well and believe there is something behind them that is intrinsically real that I can come to know personally in some way beyond the mathematical symbols. This personal knowing is a different form of knowing. It is the world of wisdom, of psyche, of spirit. Eddington as a scientist could see this, but I don’t think he fully realised the metaphorical nature of this world of immediate knowing. It is the world of relationship. It is where even the unspeakable can have meaning. It is where contradictions can be held together in a sense of unity, and paradox make sense. This is an entirely different logic from the world of science and mathematics. That environment of space and time and matter, of light and colour and concrete things, which seems so vividly real to us is probed deeply by every device of physical science and at the bottom we reach symbols. Its substance has melted into shadow. None the less it remains a real world if there is a background to the symbols—an unknown quantity which the mathematical symbol x stands for. We think we are not wholly cut off from this background. It is to this background that our own personality and consciousness belong, and those spiritual aspects of our nature not to be described by any symbolism or at least not by symbolism of the numerical kind to which mathematical physics has hitherto restricted itself. (19) This ‘background’ to which ‘our own personality and consciousness belong’ was once deeply participated in by human beings, and the remnants of this can be found in indigenous cultures. Hence their critical importance to our times, if we could only stop to enquire and listen and learn. It was the world the Romantics wanted to hold onto as the values of the Enlightenment began to to take hold of our European cultures and the seductiveness of a mechanical world view began to swamp us. It is the ignoring and denial of this personal ‘background’, that Eddington speaks of, that is the ultimate tragedy behind the climate crisis and all that we face as a world community; and institutional religion is implicated as much as technology and institutional science in this. We are heading into a time of profound unwisdom methinks. Is it too late to turn the climate around; is it too late to turn our self understanding around? This is where I think Iain McGilchrist and others are so important. They are gathering the biggest questions of life into one potential coherence I think, a universal mirror into which we might look to try and understand what needs to happen to save us. McGilchrist would say that it all depends on what we attend to. I first began to realise this with the heart many years ago when I read a book by Garry Richardson, Love As Conscious Action: Towards the New Society. In his exploration of consciousness he began by describing the experiences of three different people walking together through a virgin, fertile forest. One was a wealthy timber merchant, another was an ecologist, and the third a poet. One sized up the forest in terms of available timber and dollars and cents; the next in terms of the forest’s prolific life and complex interconnections that should be preserved at all costs; and the third ‘that behind the forest, off the path …. there is a brooding air of mystery, as if of waiting watchful sentience: a stillness, a holding of the breath’ (2) From an objective and probably self-interested analysis to a mindfulness of ‘presence’, a ‘beholding’. It all depended on what they ‘attended to’. So it is for all of us. Our consciousness, our world in which we live as persons, will depend on what we attend to. In fact we help to create the world we consciously experience through what we attend to and what we do not attend to. There are common elements in this for all of us, both in what is ‘presented’ to us in our perceptions, but also in what we ‘represent’ to ourselves in our concepts and thinking. ‘Collective representations’ are ideas, images, feelings that we all share that are part of our life together within any social unit, be it family or nation or any other grouping. Some ‘collective representations’ are empirical. In some way or other they enter our perceptual world, they are ‘presented’ to us, as well as being only in our minds as ‘representations’. Some start life as theoretical ideas that are believed collectively nonetheless; and then some empirical evidence comes through. The ‘God particle’, the Higg’s Bosun, is a classic example; where as Dark Matter and Dark Energy are still theoretical but given the sway of science are virtually ‘collective representations’. Increasingly they are thought about as real but as yet there is no empirical evidence at all. Doctrines and dogmas become ‘collective representations’, and that is how they can hold sway over a whole people. So can ‘false news’. It all depends on what authorities promulgate these ideas and concepts and help to sustain them collectively. And then we have our own experiences and our own unconscious life that inform and help to create our individual consciousness, and if Jung is right, and I think he is, this has both a personal dimension and a collective one. Then to add to all this, Iain McGilchrist puts forward compelling evidence that the two hemispheres of our brains themselves attend in different and unsymmetrical ways. We are going to look at this more closely next month. So the Wisdom Circle this month is about the importance of attention and attending in helping to determine the nature of our worlds in which we live, our consciousness, "the state of being aware of and responsive to one's surroundings." This is fundamental in accessing Wisdom and not only Knowledge. David Oliphant Homo Insapiens

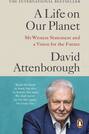

I have been reading David Attenborough’s most recent book, A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future. I can recommend it as an easy-to-read summary of the enormous challenge the human race and life on our planet faces, along with his ideas of our way through, particularly through the re-wilding of nature. At the end, in fact in one of the last paragraphs, he writes: The living world has survived mass extinctions several times before. But we humans cannot assume we will do the same. We have come as far as we have because we are the cleverest creatures to have ever lived on the Earth. But if we are to continue to exist, we will require more than intelligence. We will require wisdom (my emphasis) (Attenborough 2022:220) Attenborough is balancing intelligence with wisdom. To this point I have been balancing instrumental knowledge with wisdom. It amounts to the same thing. We now almost exclusively associate the word knowledge with what we need to act on the world in our interest, rather than what we need to relate appropriately and wisely with the world and each other. One is knowledge bestowed mainly by the left brain, the other by the right brain. Sadly though, Attenborough does not develop what he thinks wisdom is and how we can get more of it. Another interesting writer, developing the work of Iain McGilchrist, does however, or at least begins to; James Daniher. He writes of knowledge: Knowing is a left-brain activity that reduces experience to words that can be mapped into theories and beliefs that are compatible with our inherited understanding of the world. If we trust the maps and theories that our left-brain provides, God can be reduced to a knowable object to be obeyed, revered, and worshipped. If, however, we are able to still our left-brain’s rush to translate our experience into something knowable, we can experience an unknowable oneness with God that exceeds our understanding, but not our experience. (Danaher 2021:690/3000) He also introduces a beautiful concept that captures how we might grow our right brain through coming to experience the presence of what is around us in the world and each other; beholding. Beholding has become an important part of my spirituality and I continue to work on it. Beholding is a way of experiencing beauty and goodness before it is processed through the conceptual understanding of the left-brain. Beholding is a state of being rather than a state of knowing. It is the state of being present to something in order to really take it in. We are seldom in such a state in the normal business of our lives. We generally operate almost unconsciously by processing the data of our experience through the understanding the world has provided. (Danaher 699/3000) The idea of really taking something in is not new of course. Goethe believed it was the way of true science, through relationship and not only through observation and objectifying. Pay attention to something with your whole being and it will begin to reveal itself to you. He was critical of how modern science was developing in his time, with its assumption of matter and the eventual denial of the inherently personal nature of consciousness. I am hoping beholding will become something the Wisdom Circles explore in detail. But before we do that, we need to face a fundamental issue, implicit in Goethe’s and others’ critique, and which is still quite unresolved in our understanding of ourselves and the human condition; the nature of consciousness. This is where the triumph of the left brain, the emissary in McGilchrist’s terms, is most damaging and unfortunate. I only became aware of it myself in my thirties, after two university degrees. I was a true product of our modern culture. The great diarist Samuel Johnson said that science kicks a stone and assumes it is really there. That’s what I assumed also. I assumed that I experienced the world as it is apart from my experience of it. I had no idea that I played a pivotal role in creating the world that I experience, despite the fact that this is possibly one of the major issues behind the whole of our philosophical tradition. The language of matter has largely swamped the language of psyche, mind and spirit in our modern, scientific world, and yet I only experience psyche, mind and spirit directly, not matter. Briefly, the experience that awakened me was this. I was studying in Britain. One day I was walking through a wood when I came upon a stile in a fence. I climbed over the stile and as I went to put my foot down on the ground I saw that I was about to step on a frog. Just in time, I was able to move my leg and missed the frog. I then went to look, and it was not a frog at all. It was a dead leaf. But I had seen a frog. I had really seen a frog. I had spontaneously in that split second put my percept under the wrong concept and had created the image of a frog instead of a dead leaf. For the first time I had an inkling that I help create the world I experience. The significance of this might have gone unnoticed had I not been reading a book by Gregory Bateson, Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity at the time. When somebody steps on my toe, what I experience is, not his stepping on my toe, but my image of his stepping on my toe reconstructed from neural reports reaching my brain somewhat after his foot has landed on mine. Experience of the exterior is always mediated by particular sense organs and neural pathways. To that extent, objects are my creation……. It is not a trivial assertion to note that very few persons, at least in our occidental culture, doubt the objectivity of such sense data as pain or their visual images of the external world. Our civilization is deeply based on this illusion. (Bateson 1980:39) The tenor of our modern civilization under the sway of the left brain is to assert that matter constitutes the real world. We experience this world as it is through our senses. It exists quite apart from our experience of it. Consciousness is only an epiphenomenon of our material brains. As it happens, this experience has been greatly enhanced by the invention of the microscope and the telescope. We are in effect, it is believed, passive receivers of the reality of the material world at ever greater and lesser levels, from the astronomical to the quantum. The only real chink in this armour, apart from our philosophical tradition, is that reality at the quantum level seems to depend on the observer as much as what might actually ‘be there’. It takes the presence of the observer for there to be not only waves of energy at the quantum level, but also particles. In effect observing creates something. But apart from a few brave scientists such as David Bohm, the implications of this have been largely avoided. As long as the mathematics works, the parts of this ‘reality’ can be played with to enhance our power to act in the world. This is the positive feed back loop we are in in relation to our knowledge. Not only are we negating our philosophical and spiritual traditions; we are not taking seriously the full implications of our science. It was this understanding of the world that my experience of the frog that became a dead leaf eventually betrayed and undermined. Thankfully. And I am convinced Bateson is right. The illusion of objectivity at really quite naïve levels seems to hold sway in our culture, and more generally, increasingly reinforced as we build our mechanical world around ourselves. Artificial intelligence is now already part of our lives in significant ways, and its influence has barely begun. The possibility of complete alienation from nature is now imaginable. It is hard to think there could ever be a cultural tradition more blind to itself than we are. Such is the power of the Emissary currently in relation to the Master in our world. There is a push back, but it is up against very powerful forces. The epiphenomenal understanding of consciousness is now challenged by some scientists, and certainly by key philosophers. Consciousness, or what philosophy has referred to as the phenomenal world of experience, is being understood to have its own integrity and being apart from matter. Philosophically this is of course nothing new; but now some scientists are saying it, including of course McGilchrist. Even the most primitive and simple forms of life have some sort of awareness of the world external to themselves. It is this simple awareness that eventually evolved into our complex self consciousness, some contend. We are our worlds, and the part we play in their creation is as important as whatever may exist apart from us. We cannot step outside our own consciousness, and yet many factors go to constitute it. We can understand this in understanding ourselves better and balancing knowledge with wisdom. Let me finish for the moment with a quote from Iain McGilchrist. ….the most fundamental difference between the hemispheres lies in the type of attention they give to the world. But it’s also important because of the widespread assumption in some quarters that there are two alternatives: either things exist ‘out there’ and are unaltered by the machinery we use to dig them up, or to tear them apart (naïve realism, scientific materialism); or they are subjective phenomena which we create out of our own minds, and therefore we are free to treat them in any way we wish, since they are after all, our own creations (naïve idealism, post-modernism). These positions are not by any means as far apart as they look, and a certain lack of respect is evident in both. In fact I believe there is something that exists apart from ourselves, but that we play a vital part in bringing it into being. A central theme of this book is the importance of our disposition towards the world and one another, as being fundamental in grounding what it is that we come to have a relationship with, rather than the other way round. The kind of attention we pay actually alters the world: we are, literally, partners in creation. This means we have a grave responsibility, a word that captures the reciprocal nature of the dialogue we have with whatever it is that exists apart from ourselves. I will look at what philosophy in our time has had to say about these issues. Ultimately I believe that many of the disputes about the nature of the human world can be illuminated by an understanding that there are two fundamentally different ‘versions’ delivered to us by the two hemispheres, both of which can have a ring of authenticity about them, and both of which are hugely valuable; but that they stand in opposition to one another, and need to be kept apart from one another – hence the bi-hemispheric structure of the brain. (McGilchrist 2012:5) We do not experience matter directly. Only psyche, mind, spirit. Under the sway of the left brain we have culturally inverted what the ancients understood. The Emissary has usurped the Master. June 2022

Wisdom, Knowledge and the Divided Brain. In understanding and seeking Wisdom we are needing to seek to understand ourselves better, how we function and what Wholes we are part of. I have suggested there is now an urgency about this. Life on this little planet is threatened, and our actions as human beings have brought us to this point. Something has to change. How can we become wise in the use of our power that our knowledge has given us? How can we cooperate rather than compete, care rather than control? And these questions apply to us as individuals in our everyday lives as much as they apply to our nation and our world, this beautiful planet that we can now photograph as a Whole, seemingly suspended in an endless Cosmos. I am suggesting we might think of knowledge and wisdom as related poles in a continuum. Our knowledge now explores the Cosmos at the micro and macro levels, from blackholes to subatomic particles. We are increasingly surrounding ourselves with a world of our own creation by using this knowledge. Not only have we now created machines that do our bidding, we have created machines that have their own intelligence. More than that, the machine has become the model or metaphor of our understanding of everything including ourselves. We think we understand machines. After all we created them. But what we are putting at risk is our personhood and our origins in nature. What we are now facing can be seen as a fundamental clash between world views, between the world as a machine and the world as a natural Whole that is so much more than we can imagine. How can that potential clash be turned into a creative cooperation? The triumph of the machine has been a long time coming. It is not a product only of modern science. Perhaps its origin is in the first attempts to self consciously use something as a tool with which to act upon the world. It is now believed to have reached extraordinary sophistication well before the modern period. In 1901 a mechanism was found by divers off the island of Antikythera near modern Turkey. It is known as the Antikythera Mechanism. It is an ancient Greek astronomical calculator. Researchers are currently working on it and attempting to reproduce it. It is thought to date from two centuries before Christ. Not only is it an extraordinary mechanical object in itself, but it also represents the Cosmos as it was then thought to be, ‘describing the motions of the Sun, Moon and all five planets known in antiquity’. The world was already represented as a machine a long time ago. In the face of the triumph of the machine, wisdom has floundered, at least in the modern period. Some thinkers believe the last time knowledge and wisdom worked well and creatively together was in the Renaissance. But with the upheaval in values, religious and spiritual traditions, and the focus of authority that we call the Enlightenment, we have increasingly struggled to understand who we are and how we should best act. As our trust in the machine grew, our confidence and trust in our received traditions that carried our collective wisdom, was offended, to be replaced by even greater confidence that with our knowledge we can take control of any situation and prevail. Perhaps the mushroom cloud of the atomic bomb is the great symbol of the demise of wisdom, at least in the western world. On the other hand, perhaps all this has been a necessary part of the cycle we all need to go through as a human race in our need to rebuild the institutions that carry the Wisdom we so urgently need as a balance to our knowledge. Reactions have varied greatly. Some traditions have closed ranks and bunkered down against the storm. Others have tried to stay open to our evolving modern culture but still remain protective if not defensive. Still others have dared to think they not only need to rethink their own tradition but to be genuinely open to other traditions, including indigenous spiritualities. I place Open Sanctuary in this category. The challenge is to keep our own integrity while being genuinely open to truth and Spirit in other traditions. I am a man for whom Christ is central, to me personally but also to my understanding of the cosmos and history. Having this in my life I find invites me to be truly open. I am saddened that so much of the Church wants to bunker down. But I am encouraged that some of us see there is much to learn from others, and in particular indigenous spirituality. Dadirri is now part of our vocabulary. I have been watching a recent video by Bob Randall entitled Kanyini, a concept similar to dadirri but used around Uluru. The opening sequences of this video are a beautiful example of being at home in the landscape, of feeling genuinely and personally connected to all life, of life filled with solitude but never loneliness, of connection, of seeing the whole in the parts, of holding everything in conversation, of moving in the flow of life. I have no doubt that Christ lived this sort of spirituality. How different from so much of traditional church life. Can we dare to face that and work through its implications; not only the church, but all present religious and spiritual traditions. Some thinkers have called our original human consciousness participation, a felt connection in and with the flow of life, focussed in different ways over thousands of years in different forms of shamanism. That we began to progressively withdraw from this sense of participation and to separate and control and build our own world was perhaps inevitable, given the bodies and brains, and hence psyches and minds, we had inherited from the processes of evolution. Perhaps it was this inevitable separation that the ancient Hebrews captured in telling the story of the Garden of Eden. Certainly the world that Adam and Eve went into after their expulsion was the Neolithic world of cities and agriculture and crafts, not the Paleolithic world of hunter gatherers. A felt sense of participation had been compromised and the autocratic gods had been born. This possible inevitability is because the bodies and brains, and hence psyches and minds, that we inherited in the evolution of life had long been split into left and right, and this split had been entirely necessary for life to survive long before the first homo sapiens. The functions of the left and the right complement each other and need to work together. The fundamental nature of this arrangement is only beginning to be more fully understood, thanks to neuroscience and in particular the work of Iain McGilchrist et al. You can see this working together most easily in birds, because their eyes are on the side of their heads. With one eye, their right eye, they inspect the ground closely looking for seeds and worms, ready to act for their survival. The data is processed by the left hemisphere of their brain. At the same time but alternately they move their head and scan the world around to be aware of any unforeseen danger. They do this through their left eye and their right brain, again for their survival against predators. The right hemisphere takes in the whole they are part of; the left the part they wish to control and capture for their use. Our brains and bodies, and hence psyches and spirits, are developed versions of these processes of discernment, awareness and capacity to attend. When they work together we have both a sense of the part and the whole, and this is a very creative place. But the relationship is not symmetrical. The functions of the right brain need to have precedence over the left if the mind is to function creatively; wisdom needs to guide knowledge. That is the rub. We are living in a world now where the left hemisphere has usurped the precedence of the right. How do we redress this crisis? How do we re-find a sense of lived participation and spontaneity in the Cosmos while at the same time valuing and understanding our knowledge by saying ‘No’ to technology and actions that are unwise to accept and take up, and instead rest at peace with gratitude in and for our wise Being. These are the things we will slowly explore and practise in our Wisdom Circles at Open Sanctuary. Now let me finish with some quotes from McGilchrist’s essay The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning. What are the key distinctions? One way of looking at the difference would be to say that while the left hemisphere's raison d'être is to narrow things down to a certainty, the right hemisphere's is to open them up into possibility. In life we need both. 13 The left hemisphere, as in birds and animals, pays the narrow-beam, precisely focussed, attention which enables us to get and grasp: it is the left hemisphere that controls the right hand with which we grasp something, and controls the aspects of language (not all language) by virtue of which we say we have ‘grasped’ the meaning – made it certain and pinned it down. The right hemisphere underwrites sustained attention and vigilance for whatever may be, without preconception. Its attention is not in the service of manipulation, but in the service of connection, exploration and relation. 12 We had modelled the brain as part of a machine, the hemispheres as mechanical parts of a mechanical body. There are, of course, only two possible models: seeing it (the brain) as part of a machine or as part of a person. 9 Bob Randall’s video can be found at https://youtu.be/JyJ0Izztq28 David Oliphant  Tilba Wisdom Circle at Open Sanctuary 14th May 2022 The first Wisdom Circle at OS was held in March, where the whole theme and idea of a regular Wisdom Circle was outlined. Wisdom was seen to be, amongst other things,:

My reason for wanting to establish a regular Wisdom Circle is the belief that we in the World, at both local and global levels, are facing an enormous moment of truth. We are knowledge rich and wisdom poor. We have never known more about the ‘what’ of the world, and seemingly never understood less about the ‘how’ of the world. Our actions can now be devastatingly powerful, but we don’t seem to know how to act to save ourselves. It is as if we are entrapped in an incapacity to act together for our own good as a human race. We are like an assemblage of individuals, of parts, each beating its own drum, rather than the one human race, a Whole that is more than the sum of its parts. The enormity of the future we are facing is not getting through to all these parts. Why is this happening? What are we missing? In that first gathering I suggested that we are running out of excuses for avoiding the Whole and wanting only to live for much lesser wholes. We are running out of excuses because our World, our little Planet Earth, is now an object in the Universe not only in our imagination but to our actual perception, in immediate experience for space travellers and through photographs for the rest of us. One of the most famous photographs ever taken, Earth Rising at Christmas, taken in 1968 was but the first of now countless photographs of Planet Earth, each enabling us to understand our ‘home’ as an object over and against us but in which we, each one of us, at the same time are part. Our world can never be the same, and unless a human colony is formed on another planet somewhere, this is it. We make this one work or we have had it! We really and truly need to balance our knowledge with wisdom. Photographs of Planet Earth floating in the Universe are symbols of an ultimate Whole we need to be living for and with. This understanding of the Planet as a Whole that now must demand all our attention points to the importance of the 4th dot point above, making decisions with the well-being of the whole in mind. What are some of the implications of this great shift, for us as individuals, for us as Australians, for us as largely descendants of European cultures in the new world, and so on. But also for us as organizations, businesses, governments. There is a paradigm shift here that has the potential to transform. More than that, are there other Wholes as well we need to be more aware of, perhaps of at least equal importance waiting to emerge, that are implied I believe in the Whole that is our Planet Earth. For instance, if we can look at Planet Earth and admit to ourselves that we are all human beings needing to live together if we are to survive, can we also see that we are all participants in the one Story of how we got here. This brings in the 5th dot point above, deeply understanding the human and cosmic situation, mankind’s experience, and human nature. Let me unhesitatingly suggest that this Story is another essential Whole to become more aware of in finding greater wisdom. I suggest that these 4th and 5th points might well be the key points in our list that in turn help to enable the other points that make up Macdonald’s understanding of Wisdom. It doesn’t stop with Story. When Copernicus provided data that supported the idea that the sun and the planets did not go around Planet Earth but rather we all went around the Sun, a new sense of World began to dawn in European consciousness, at least in imagination. The word World was in fact emerging in the developing English language to translate the word Cosmos in Greek. It meant literally the Age of Man. We began to believe the World could be mapped long before it could be photographed. Mercator produced one of the first maps of the World. This change in perspective or concept was part of the general move toward our increasing sense of self as individuals, that we each stood over and against the world and it over and against us, as individuals; that we are microcosms of the macrocosm. Just as all the parts of our being constitute a whole, so all the parts of the World constitute a whole. We mirror each other. So you and I, we are all Wholes to be taken seriously as well, and not only parts. Wholes within wholes. Understanding ourselves as Wholes in both space and time is ideally the focus of all three great poles of human experience and exploration, science, art and religion. Each focus is from a different point of view. But currently, and for some time, these three poles have been fighting and misunderstanding each other, just as people generally have been fighting and misunderstanding each other. Science has developed scientism, religion fundamentalism, and art surfacism. We have been progressively losing a sense of the depth of our being and our connection with the Cosmos, something many Indigenous peoples still have. There have been many who have been pointing these sorts of things out, some in a general sort of way such as Jo Marchant in The Human Cosmos, others in a profound way such as David Bohm in Wholeness and the Implicate Order and other works. We can learn from them in coming to understand our situation better, and the need for Wisdom to balance Knowledge. One thinker in particular is coming to the for at the moment, Iain McGilchrist. He has just published his magnum opus The Matter With Things following an earlier book The Master and His Emissary. We will be dipping into these two books in the Wisdom Circle in gentle bites for some time. Where I think McGilchrist is genuinely very important and helpful is that he brings together the spiritual and psychological with the material, in other words Mind with Brain, Body with Consciousness, Action with Spirit. In the whole of the modern period in our European traditions these have been irreconcilable, if not rent asunder. He has done this by returning to the differences of function between the two hemispheres of our brains, something that became popular 40 to 50 years ago but was then discredited by neuroscience as a reaction. McGilchrist, as a neuroscientist and psychiatrist and thinker, is saying, in effect, ‘lets get the baby back and let the bathwater go; in understanding the way the brain works will help us understand our minds and consciousness and how these have evolved to our current situation’. All this might sound a bit heavy. Don’t be put off. My intention, and those helping me, is to make it all interesting and digestible, and more importantly tie it into the practice of silence and contemplation and prayer, a finding or re-finding of depth, in understanding who we are and where we have come from on this little Planet Earth; and our options for the future, globally and locally. David Oliphant  Dear Friends and Friends of Friends of Open Sanctuary I am writing to warmly invite you to our first Wisdom Circle in 2022. It is to be held at Open Sanctuary (the old All Saints Church on Corkhill Drive between Central Tilba and Tilba Tilba) on Saturday 19th March beginning at 3pm. Everyone is welcome. As most of you will know, Open Sanctuary is a contemplative community, sensitive to spirit, Country and environment. On many occasions Linda has encouraged us to practice ‘deep listening, a spiritual skill, based on respect. Sometimes called 'dadirri', deep listening is inner, quiet, still awareness, waiting – and available to everyone’. The indigenous practice of dadirri increases our awareness of ‘what is’ around us, and can lead to a sense of inner participation in the energies and images that make up our world. There are those who see this sort of practice as ‘The Aboriginal Gift - Spirituality for a Nation’ that is ours to accept, something that would help us meet the emotional and spiritual challenges of our own time here in Australia. The Aboriginal Gift - Spirituality for a Nation is the title of an important book by Eugene Stockton, and more recently a talk given by Dr David Tacey through the Eremos Institute. I believe in our own way we at Open Sanctuary are accepting and working with this great gift. In my own life I have come to value enormously this sense of participation through deep listening and waiting. I have come to link it to the original consciousness that perhaps characterised our experience when we humans lived in the paleolithic. There was little veil between our inner and outer worlds. Our psyches activated easily and we thought spontaneously in metaphor. Wind, breath and spirit were all one experience. There are times when I feel the fluttering leaves in the tree, caressed by the breeze, as movement and energy within myself. I feel alive and connected. In this sense of connection I have taken to talk to the world around me. I often pass cows in the paddock on my walks, and they stare at me ‘knowingly’ as I talk to them. I imagine their lives as mothers and little calves. I have come to cherish that different trees have different characters. They have presence. They ‘talk’ in different ways. Even rocks have presence when I am in that dadirri spacetime. I am attaching a photo of me talking to my favourite rock. And looking into the night sky I imagine the fascination of the ancients in the mystery before them, looking for movement and patterns, signs and portents, but most of all feeling surrounded by and fully part of the mystery that is sometimes exhilarating, sometimes terrifying. I am not having a separate experience in my isolated self; I am sharing in Experience far greater than myself. I love all that dadirri and similar concepts and practices stand for, and so grateful to have come to know about it and be guided in my spirituality by it. But I am also a child of our own age. How different. We live at the other end of history to the paleolithic. We have been on a huge journey as human beings in which we have increasingly separated ourselves from the Cosmos, from the world around us. We have come to know the world not personally and subjectively but impersonally and objectively. With this knowledge we have acted upon our world to shape it to our wills and wants. We have abstracted the physical world, the world we can measure, from our phenomenal world, the world we experience as human beings, and reduced it to mathematical formulae which enable us to predict and experiment to our own advantage. Modern science is without a doubt a great triumph. But there is an enormous cost to this triumph that needs to be redressed. The idea of a Wisdom Circle for me has arisen as a response to what is happening in our world, both locally and globally. We have reached a point in our history when we have unprecedented knowledge and technology, but we don’t seem to know how to act. We court disaster not knowing how best to act. Many think we just need more scientific knowledge and technology, and then we will be all right. But scientific knowledge and technology can empower our actions but cannot tell us how best to act. For that we need a different sort of knowledge, a knowledge that does not only work with the parts but a knowledge that also has a sense of the whole. Wisdom enables us to act in a way that is best for the Whole. There are many wholes in our lives. A relationship with another person is a whole; wisdom is knowing how best to act in a way that is of benefit to both persons. A family is a whole; being a wise effective parent is to know how to act in a way that is of benefit to all the members of that family. Work places, associations, clubs, churches, organisations are all wholes made up of parts. They work for everyone if the leaders are wise and everyone bears the interest of the group at heart. States and countries are wholes needing wise leaders who inspire trust and goodwill. Our planet is perhaps now our most significant Whole, and this is where there is a major shift from the past. The paleolithics lived within the mystery. They had little or no sense of planet Earth as we do. Since space travel and the circulation of actual photographs of our beautiful Home in our vast Universe, we have been able to see and imagine this most significant Whole as never before, Planet Earth. This is the symbol that will centre our Wisdom Circles at Open Sanctuary. This symbol will not only centre our thoughts and feelings now in what is happening in our lives and in the world, but will also focus our thoughts and feelings about our whole story as a human race. Sounds big? I guess it does, but we will only bite off bits at a time. Whereas the ancients once looked unguarded into the majesty and mystery of the heavens and balanced this with descent into the womb of the earth in rock shelters and caves, we now ascend above the Earth in imagination and vicarious association with those who have travelled space and stood on the Moon, to view the Whole that is our home in an endless SpaceTime and to ask ourselves the big questions of how it is now best to act. And we seek the Wisdom of the Whole that lies within the vast structures of our unconscious psyches, gifted to us by the evolution of matter and consciousness in the great Story that brought us here. Underneath the clash of identities that marks our public and private lives now is the undeniable fact that we are all human beings in One World, parts of the One Whole. We all share the same underlying identity. How then can we best act locally and globally in ways that will be of benefit to this One Whole. How can we then use our science and technology to empower our actions? This is what the Wisdom Circle is exploring. We need to do what we need to do, in our own little ways, trusting the Mystery. At the time of writing the World has been plunged into the possibility of a Third World War that would be the result of one man’s complex foolishness and cunning, however much he thinks his own country might benefit. Cunning is invariably self-interested and ego-centric. It is the opposite of Wisdom. Wisdom dares to love, dares to trust, dares to be open. At our first Circle on March 19th we will look at Wisdom in an introductory way. In our second Circle on the 2nd Saturday of April we will be honouring Noel Davis, one of nature’s wise persons and long time member of Open Sanctuary, who died a year ago. Noel is buried at Open Sanctuary. His memory is honoured amongst us; his spirit is alive and well. We will be welcoming and blessing the completion of his last book of poems, organised and published by Trish Delaney. Hope to see you there at both occasions. David Oliphant PS. This is me talking to my favourite Rock |

AuthorDavid Oliphant Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed